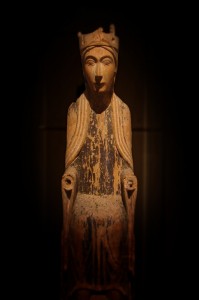

From the medieval collection at the Metropolitan Museum of Art. It's a Madonna, but it might as well be Rebekah. Photo by Rick Morley

Genesis 25 moves quickly. If you lift your eyes from the page you just might miss a few decades.

In less than fifteen verses Jacob and Esau go from zygotes to teenagers. And yet, not much changes in those verses, or in those years: Jacob and Esau are very different creatures in the womb and very different creatures outside of the womb.

Like their forebears Cain and Abel, one is refined and the other is a brute. Not that anything is wrong with either of those two, it just seems that, biblically speaking, that’s a bad combination.

A tragic combination.

However while the refined Abel was ‘done in’ with a blunt rock to the skull, the refined Jacob comes out on top with his sibling.

And no rock needed. Just a pot of beans.

I’ve done a lot of thinking lately about the stories of Genesis and how they found their own origin in oral tradition. These stories were told over campfires, and passed down through the generations from parents to children long, long before they were ever written down.

It’s why the stories have so much color to them. Their tragedy is relentlessly tragic. Their comedy is overwhelmingly funny–if we can get past their stilted and stained-glass English translations.

Obviously the cartoonish differences between Esau and Jacob were part of the oral canon that the descendents of Jacob told to laugh at the descendants of Esau, the Edomites.

The punch-line is that the great-great-grand-daddy of the Edomites was a hairy, brutish, blue-collar dunce who sold his most valuable possession for a bowl full of bean stew.

Or, “red stuff.”

You better believe that always got a raucous laugh every time that line was fed out over the crackle of the bonfire.

In the big picture, this is more of a story of two nations and their distaste of the other. Like a good college basketball rivalry, the legend is bigger and better than the reality.

As long as you’re on the winning side.

My guess is that the Edomites had similar stories that they told around their campfires. Maybe they were about how much of a sissy Jacob was.

Regardless, where I identify with this particular story is in how dysfunctional it all is. Sometimes I think we feel like we have to project to the world–and certainly to the neighbors–that our family, our home is “normal.”

Everything is alright.

It’s fine.

But, this story reminds me that it doesn’t have to be fine. Nothing has to be fine.

Things can be awful and embarrassingly dysfunctional–and God can still move. God can still do great things.

I really believe that at the heart of the stories of the patriarchs, and the whole of the history in in the book of Genesis, is the truth that God does things through the lives of the strangest and most awkward of people.

When God looked out over the whole world to find the people he would call his own–the people he would bless with the privilege of being a blessing to the whole world–he chose what often times looks like the “b” team. The replacements. The ones who didn’t even have the illusion of having their act together.

He chose people—Just. Like. Us.

And deep down between all the guffaws and revery of the campfire, that’s the message that our forebears got night-in and night-out: We don’t have to be perfect and have everything figured out and in flawless order before God can visit us, and bless us.

In fact, we can be a blessing to the whole world.

If God can work in the household of Isaac, Rebekah, Esau, and Jacob–then my goodness, there is no doubt that God can work with us too.